Opera in three parts by George Benjamin on a text by Martin Crimp. Premiered at the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence on 7 July 2012.

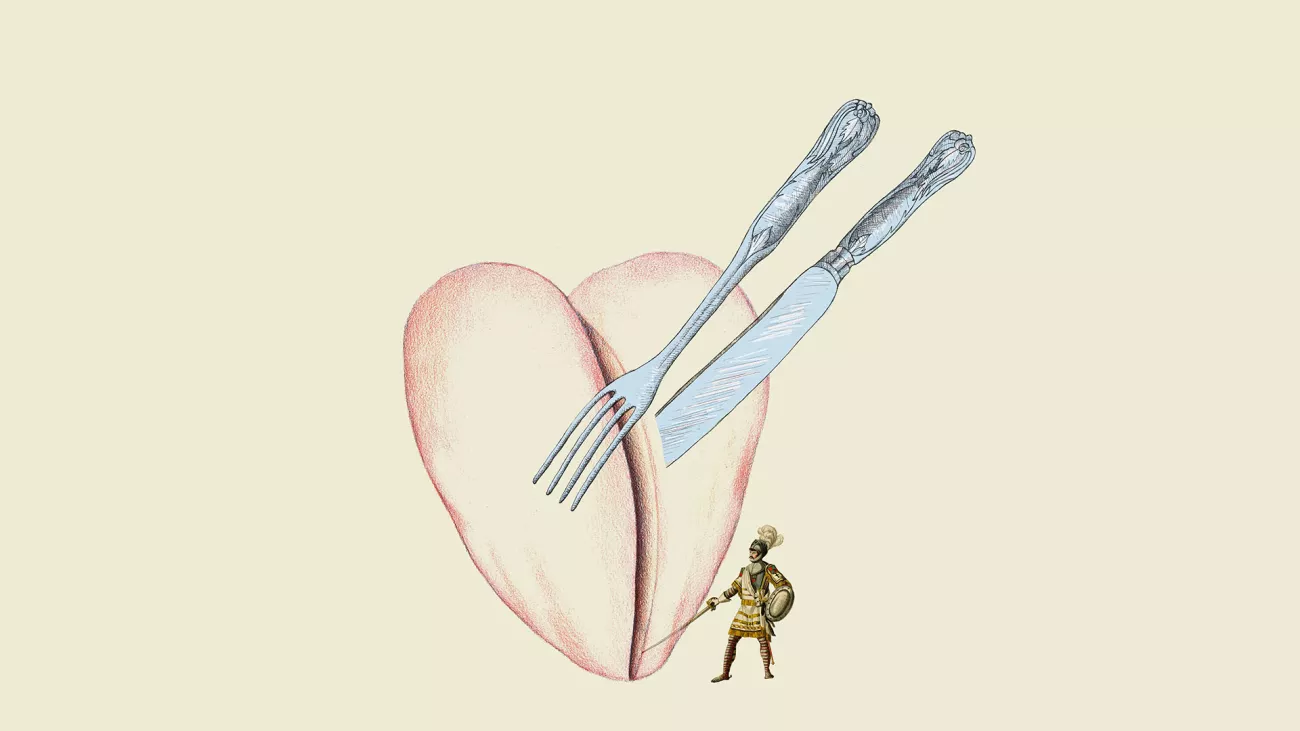

The premiere of Written on Skin was the operatic event of 2012, proof that opera can move contemporary audiences through its capacity – that might prove to be stronger than cinema – to adapt past subjects and the great motifs of our culture to present preoccupations. With Written on Skin, Martin Crimp and George Benjamin transfigure the medieval fabliau of the eaten heart as a parable of desire.

The traditional love triangle is somewhat shaped by experience through a dialogue which absorbs the narration, the breathtaking unfolding of the theme of illustration and the hypnotic dramatic ceremonial designed by Katie Mitchell. What glory does the lord of the place aspire to? What does the illuminator really intend to draw in his home? What recognition does the wife, Agnes, expect? What delicious dish can forever prevent her from eating? What is that skin on which the story is being written? For the first time in the history of opera, the driving force behind the drama is no other than women’s pleasure.

Opera with english subtitles

Performance duration 1h40 without interval

Presentation of the work by Agnès Terrier 40 minutes prior to each performance

France Musique will broadcast Written on Skin live on the 19th november 2013.

Video of the opera Written on Skin de George Benjamin created in the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence in july 2012 realised by the Festival d'Aix

PART ONE

I. The Choir of angels

A choir of angels brings us back eight centuries ago when each book was precious and “written on skin.” They embody two of the main characters of the story: the Protector, a landowner, and his obedient wife. One of the angels becomes the third protagonist, the Boy, an illuminator of manuscripts.

II. The Protector, Agnès and the Boy

In the presence of his wife, the Protector asks the Boy to solemnize his life and good deeds on an illuminated book. As proof of his talent, the Boy shows a miniature to the Protector, the flattering portrait of a wealthy and merciful man. Agnès mistrusts the Boy and the art of pictures alike but the Protector orders her to welcome the Boy.

III. The Choir of angels

The angels recall the violence of the creation of the world as depicted by the Bible and its hostility toward women.

IV. Agnès and the Boy

Unbeknownst to her husband, Agnès goes to the Boy’s workroom to see “how a book is made.” She challenges the Boy to make the portrait of a “real” woman like her. A woman he could desire.

V. The Protector and the visitors, John and Marie

As winter approaches, the Protector is preoccupied by the change in his wife’s behavior. When Agnès’s sister, Marie, arrives with her husband, John, she wonders if the making of such a book is proper and if it is wise to invite a stranger at the family table. The Protector stands up for the book and the Boy and threatens to drive John and Marie away from his lands.

VI. Agnès and the Boy

That night, while Agnès is alone, the Boy enters her room to show her the painting she requested. As they are examining the painting together, sexual tension rises until Agnès gives herself to the Boy.

PART TWO

VII. The Protector’s bad dream

The Protector dreams that his people are rebelling against the price of the book but also of a rumor that the book contains a secret page “wet as a woman’s mouth,” in which Agnès is seen “attracting the Boy into a secret bed.”

VIII. The Protector and Agnès

The Protector awakes from his dream and stretches his arm toward his wife. She asks her husband to touch her but he spurns her. She refuses to be treated as “a child” and tells him that if he wants to know the truth about her, he should go and see the Boy.

IX. The Protector and the Boy

The Protector finds the Boy in the wood. He forces the Boy to reveal the name of the woman who “screams and sweats with [him] in a secret bed” – is it Agnès? The Boy, who does not want to betray Agnès, confesses that he sleeps with her sister, Marie, and makes a preposterous description of Marie’s erotic fantasies. The Protector is more than willing to believe the Boy and tells Agnès that the Boy sleeps with “the whore who is her sister.”

X. Agnès and the Boy

Agnès, who is furious, accuses the Boy of deception. He retorts that he lied to protect her – but this only increases her anger. If he truly loves her, he must have the courage to tell the truth and punish her husband. She asks the Boy to make a powerful and shocking picture that will destroy her husband’s self-importance once and for all.

PART THREE

XI. The Protector, Agnès and the Boy

The Boy presents some pages of the completed book – a collection of atrocities – to the Protector and Agnès. The Boy claims that those are pictures of Paradise on this earth – does the Protector not recognize his family and possessions? Then Agnès asks to be shown Hell. The Boy gives her a written page, which throws her into frustration since, being a woman, she was not taught how to read.

XII. The Protector and Agnès

The Protector reads the written page aloud. In it the Boy describes his affair with Agnès. The Protector is overwhelmed by the revelation whereas Agnès hears confirmation that the Boy did exactly what she asked of him.

XIII. The Choir of angels and the Protector

The angels recall the cruelty of a god who creates man from dust only to fill his mind with contradictory desires. Torn between mercy and violence, the Protector returns to the wood and kills the Boy.

XIV. The Protector, Agnès and the angels

The Protector tries to reaffirm his authority over Agnès. He forces her to eat a dish as token of her “submission.” He then tells her that she has eaten the Boy’s heart. Far from killing her will, this brings about one last burst of rebellion and Agnès declares that no act of violence will ever erase the taste of the Boy’s heart in her mouth.

XV. The Boy/Angel 1

The Boy reappears as an angel to present one last picture: the Protector grabs a knife to stab Agnès who chooses to jump from the balcony to her death. She can be seen falling while three little angels painted in the margin turn around to face the audience.

Opera is an old genre nowadays: it has become optional for composers – whose careers formerly rested on the prestige of opera – and for the public – whose range of entertainments and social practices has widened enormously. To create an opera in the 21st century is all the more challenging: the venture suggests a deep need for narrative and drama in the musician, sharing and cultural emulation in the audience.

Today each operatic creation rests on the search for a strong inner coherence and a profound meaning that goes beyond the contingencies of representation. Opera is no longer an entertainment, the celebration of a social community or a complete work of art. It claims to be a way of grasping and questioning contemporary sensibility.

Written on Skin is among the most beautiful fruits of this novel approach that focuses less on opera in general and more on the work in particular.

Commissioned by the Festival d’Art lyrique of Aix-en-Provence, where it premiered on 7 July 2012, Written on Skin mobilized two great British creators: the playwright Martin Crimp, a figure of contemporary English drama translated into many languages, and the composer George Benjamin, whose highly stimulating musical world draws strength from a free and fruitful connection with the great Western tradition.

The libretto draws its subject from a Provençal medieval legend that became a literary motif: the eaten heart.

Presented as a biography, this short story is based on the work of an early 13th century noble poet, Guillaume de Cabestaing, whose seven poems in Occitan are all that which has survived. The lover of Lady Sermonda, Cabestaing is thought to have been killed by her jealous husband, Raimond de Castel Roussillon, and his heart offered as a dish to the lady who died thereafter.

By the second half of the 13th century several versions of the story glorify the love bond between the lovers and their profound fidelity. The husband’s downfall, moral at first and then decreed by the king of Aragon, aims to make courtly love sacred. The lover, a troubadour in Southern versions, becomes a valiant knight in the German version by Konrad von Würzburg (the Meistersinger in the famous Swan Knight – Lohengrin) and in Jakèmes’s Picard version, the Roman du châtelain de Coucy et de la dame du Fayel. Later, Boccaccio made it a short story in his Decameron, the Renaissance utilized it and Jean-Pierre Camus adapted it to the genre of his Histoires tragiques in 1630. By the end of the century of Enlightenment, Pierre-Laurent de Belloy successfully premiered his Gabrielle de Vergy at the Comédie-Française during the blossoming of horror drama. While Donizetti drew his opera Gabriella di Vergy from it, Stendhal revived it in Le Rouge et le Noir and in De l’amour (On Love) before the Marquis de Sade and Barbey d’Aurevilly rekindled its cruelty.

By reinforcing the original Provençal reference, the text of Written on Skin fits in with today’s renovation works that have animated the city center of Aix-en-Provence these last years. These works resulted in the appearance of a new neighborhood around the Grand Théâtre de Provence, a building inaugurated in 2007 where Written on Skin was premiered in a production by Katie Mitchell and accompanied by the Mahler Chamber Orchestra conducted by the composer.

Thus, Written on Skin can be likened to an archeological gesture which consists in removing the asphalt of our streets in order to revive the feudal world of large estates and lords haunted by their salvation and the survival of their lineage and renown. One of these great landowners is the first protagonist in the opera, the Protector.

In that world, troubadours, scholars and illuminators shape medieval history, whether they extol the great feats of the past or illustrate contemporaneous deeds for future generations. The second protagonist in the opera, a young illuminator called the Boy, belongs to this caste of artists who master the techniques and issues of representation.

Since these artists always work in accordance with the will of God, exalting his presence and actions in all things, they share certain attributes with the angels, the ministers of Heaven. In the opera, the Boy can see into the future: the urban realities whose strata will cover his story and the Protector’s. The Boy is played by a vocalist who also assumes the part of an angel. Two other angels help him organize and comment what happens on stage, unless they also put on his costume in order to perfect the ceremony.

To entrust angels with the framing of the story and the temporal tension that pervades the work, Martin Crimp relied on a passage by German philosopher Walter Benjamin from his Theses on the Philosophy of History: “There is a painting by Klee called Angelus Novus. It depicts an angel who seems to be about to move away from something he is gazing intently. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open and his wings are spread. This is how the angel of history must look. His face is turned toward the past. Where we see a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe that unceasingly heaps ruins upon ruins and flings them at his feet. He would like to stay, awaken the dead and reassemble what has been shattered. But a storm is blowing from paradise which has been caught in his wings, and it is so strong that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly drives him into the future to which he turns his back, while the heaps of ruins before him pile up to the sky. This storm is what we call progress.”[

Written on Skin is suggestive of parchment – animal skin that preceded paper in the West and resulted in the development of written literature and illustration thanks to its smoothness and strength.

By making the original troubadour an illuminator, George Benjamin and Martin Crimp endowed the Boy with a crucial part: that of bringing to light, both literally and figuratively. The arrival of the Boy and the fulfillment of the representation that glorifies the Protector trigger a process of irreversible revelation.

The character that undergoes the deepest transformation is that of the wife, who is metamorphosed from object into subject. Another, more real story is written on skin. As the only character to have a name, Agnès embodies access to the status of individual, one of the great advances of the Middle Ages which pervaded society and the arts. But at the core of the work, her conquest of carnal pleasure resonates more widely with the modern world in which the evolution of women’s status turns out to be discordant and uneven.

With the deliberate choice of this bold perspective on the human condition, Martin Crimp and George Benjamin made Written on Skin an opera that is novel, profound and essential.

Music direction, George Benjamin • Staging, Katie Mitchell • With Christopher Purves, Barbara Hannigan, Iestyn Davies, Victoria Simmonds, Allan Clayton, David Alexander, Laura Harling, Peter Hobday, Sarah Northgraves • Orchestra Philharmonique de Radio France

See all the castSaturday, November 16, 2013 - 8:00pm

Monday, November 18, 2013 - 8:00pm

Tuesday, November 19, 2013 - 8:00pm

1:40 - Salle Favart

110, 87, 67, 41, 15, 6 €

Cast

Angels, Archivists, David Alexander, Laura Harling, Peter Hobday, Sarah Northgraves

Orchestra, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France

Associate production, Festival d'Aix-en-Provence

Commission and co-production, Festival d'Aix-en-Provence, Nederlandse Opera Amsterdam, Royal Opera House Covent Garden London, Théâtre du Capitole de Toulouse

Co-presentation, Opéra Comique, Festival d’Automne à Paris

Publising, Faber Music Ltd

Partnership