OPERA-COMIQUE in three acts by Ferdinand Hérold. Livret by Mélesville

First performed at the Opéra Comique on the 3 may 1831

In 1830 the Revolution of the Trois Glorieuses (the Three Glorious Days) leads to a new regime, the July Monarchy, and enthrones Louis-Philippe as “king of the French”. Berlioz enthusiastically orchestrates La Marseillaise and sings it on the barricades. The Parisians discover Beethoven at the Conservatoire concerts. Victor Hugo has just shaken up the Comédie Française with his Hernani and Nerval has overturned the young lions with his first translation of Goethe’s Faust. While an English troupe reveals Shakespeare to the patrons of the Odéon theater, Rossini and Schiller enlighten subscribers of the Opéra with William Tell’s fate. In Brussels, Auber’s La Muette de Portici brings about the insurrection that leads to Belgium’s independence. The wind of revolution is blowing in all directions. A new generation, that of the children of the Empire, wants to take the lead in a materialistic and resolutely bourgeois society. To upset conventions, strike the imagination, impress the crowds – to live! Such is the impulse that drives French romanticism at its inception.

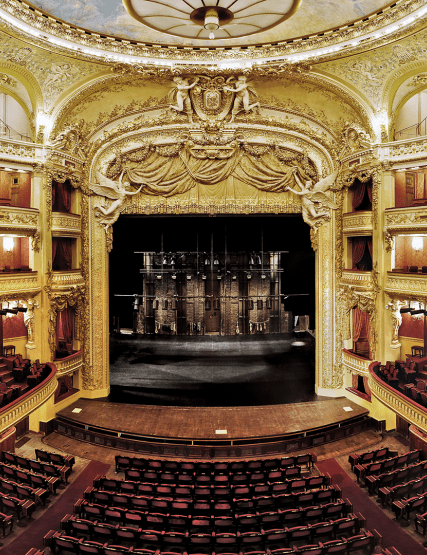

Social comedy is in full swing in theaters. Lorgnettes and opera glasses are conspicuous. Under the brightly illuminated chandeliers, to enthrall their subscribers, directors invest in golden voices, magnificent stage sets, lighting effects through recently installed gas pipes, choral sections, ballets and crowd artists, and advertising pretty soon.

In the preface to his Cromwell, Victor Hugo enjoins to “skim through the centuries” so as to “revive the past.” In effect, with the advent of the

historical novel, opera houses favor historical themes for their inexhaustible dramatic and ornamental potential. A new vein from Germany and England feeds French romanticism, namely the fantastic, so that drama can display musical and staging boldness. By trying to combine historical and fantastic themes, a clever librettist would take to a medieval subject. As a highly superstitious period, the Middle Ages are very popular in the nineteenth century as evidenced in works by Michelet, Hugo and Viollet-Le-Duc as well as the fashion of neo-Gothic and troubadour styles.

What do we know of those archaic times that preceded the age of order and reason established by Louis XIV? All that which Zampa stages in 1831.

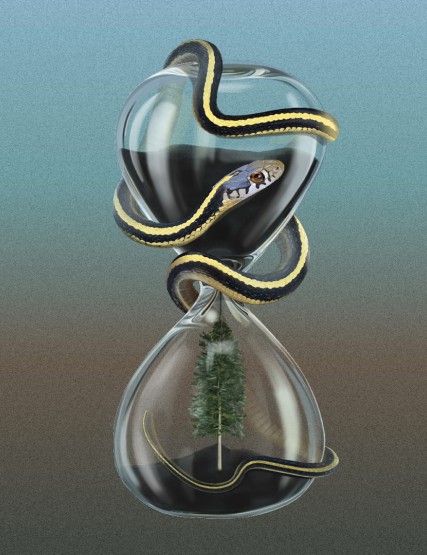

The Romantics are perfectly aware that prior to Enlightenment Europe was dominated by fear: fear of the Devil and the great plagues, of war and armed gangs, of the sea and the night, of the Turks and curse. All these fears join in the Sicilian village where Camille lives. Life and death are intertwined: catechesis and superstition entertain doubts quickened by religious iconography. The fishermen are under the protection of a dead woman killed by a pirate. In case of danger, her statue moves as a warning, thanking them for their hospitality. One day the pirate disembarks: he takes after Faust for his rejection of all morals, Don Juan for his irresistible seductiveness, the Flying Dutchman for his intrusion. He’s damned romantic.

Drawn from Molière’s Dom Juan, this wonderful theme is written by librettist Mélesville. Emile Lubbert, the new director of the Opéra-Comique, has a leaning for a talented and experienced fortyyear old composer, Hérold. Recently set up in comfortable but costly Salle Ventadour, the Opéra-Comique undergoes a critical period. Because of financial hardships, the theater closes several times and the director is changed twice within a year. In addition, the repertoire gets outdated, competition arises from the Boulevard theaters with similar productions, and it lies in she shade of the Opéra. In late 1829 Meyerbeer withdraws Robert le Diable from the Opéra-Comique and gives it to the Opéra which is then directed by… Emile Lubbert! When the latter becomes director of the Opéra-Comique, he constantly endeavors to find such a brilliant theme. He finally chooses Hérold, a composer of comic operas and choral director at the Opéra in private. For the first time, the perviousness between the two institutions advantages the Opéra-Comique as Zampa is ready a few months before Robert le Diable.

Zampa has its premiere on May 3, 1831 at Salle Ventadour. The staging is handled by manager Solomé, purposely lured away from the Comédie Française . Solomé designs Gothic sets and costumes, a beautiful articulated statue of fake white marble which he cashes in on beyond price at reprises in other theaters since, according to him, “the whole play lies in that statue.” Finally, the numerous lighting and smoke effects are operated by a pyrotechnist and a light maintenance man to depict the volcano – a symbol of romanticism par excellence (“Your head seems to be an evererupting volcano,” wrote Rouget de Lisle to Berlioz).

It is an immediate success with the outstanding medley overture. Musically, “this score meets all the requirements today in Paris for a true comic opera” (Berlioz) and reflects great credit to the talented artists of the troupe, especially Madame Casimir as Camille and majestic Cholet as Zampa.

Zampa runs for fifty-six nights and was to be performed almost seven hundred times till the end of the century. Numerous singers were eager to add the title role to their repertoires, gratifying both tenors who could baritone and baritones singing as tenors. The work was soon performed abroad: Brussels and Vienna by 1832, London, Naples, Turin and Moscow in 1834, then Germany. During his stay in Vienna in the summer of 1832, Richard Wagner was exasperated: “Anywhere I went, I could hear Zampa and Strauss’ potpourris on Zampa! These two things –and especially at that time– were an abhorrence to me.

An “abhorrence” for a few elitists, Zampa was moving and efficient, romantic and popular. In this it accomplished the mission assigned to drama by Victor Hugo: to be a landmark for its time.

Act I

In early sixteenth century Sicily in merchant Lugano’s palace the wedding of his single daughter with Florentine officer Alphonse of Monza is about to take place. As the lord is late Camille heartens her lover: he is not wealthy, but has he not deserved to marry the best catch in Sicily by rescuing his future father-in-law from the brigands? The region is still insecure even though Zampa is said to have been arrested. The terrible pirate has ruined the honor of many a family and the population is under the protection of Saint Alice, after the name of one of his victims, Alice Manfredi, whose statue recalls the cruel destiny of a seduced girl who was abandoned and then died of despair on a Sicilian shore.

Hearing the story for the first time, Alphonse realizes with terror that the pirate is none but his elder brother, a rake who disappeared in his childhood. A stranger bursts into Camille’s room as she’s alone. Lugano has fallen into his hands. He demands her properties and a shelter inside the castle. Fearing for her father’s life, Camille postpones her marriage and gives up the household to the stranger. It soon turns out that the latter is Zampa himself who devises a new scheme: add Camille to his numerous conquests. Before the statue of Alice, his first mate Daniel warns him: past crimes might catch up the seducer. To cheer up his companions, Zampa places a ring on the statue’s finger. To the dread of all, the marble hand closes around the jewel.

Act II

The following day the village sinks into terror while the new master and his men are still unidentified. In front of the chapel, Zampa is watching for Camille, determined to marry her and ignoring Daniel’s fears. The freebooter is laughing at it all: as long as Lugano is his prisoner, Camille won’t denounce him. Alphonse has escaped an ambush and is back only to learn the cancellation of his marriage. What could have so upset his happiness? Does Lugano prefer another son-in-law? Coming out of the chapel, Camille dares not confess the nasty blackmail. Alphonse decides to gather his men so as to face the intruders and thwart the new wedding. At the sight of the menacing statue of Alice, who brandishes the ring to remind the pirate of his oath, Zampa leads Camille to the altar. Thanks to the description of the villain, Alphonse identifies Zampa and is about to deliver him to the angry populace. But a dramatic turn gives the advantage to the corsair: the viceroy promises to pardon Zampa in return for his rallying against the Ottomans. While the people celebrate their new protector, Camille has no choice but to marry her father’s kidnapper.

Act III

In the evening after her wedding Camille awaits her father, but Alphonse arrives to abduct her. She refuses, putting forward her having sworn to God and Zampa’s promise. Before meeting with his wife, the freebooter asks Daniel if the statue has been broken and thrown into the sea. Camille asks Zampa to keep his promise and tells him about her intention to go into a convent. Zampa is infuriated at the thought that Camille is appalled to marry a bandit. He then reveals his true identity: count of Monza, Florentine lord. Camille can but appeal to Alice Manfredi. The statue appears again and drags Zampa own to hell while the Etna is ablaze.

William Christie / Jonathan Cohen*, Jérôme Deschamps, Macha Makeïeff

With Richard Troxell, Colin Lee, Jaël Azzaretti, Léonard Pezzino, Doris Lamprecht, Vincent Ordonneau

Comédiens, Luc Tremblais, Laurent Delvert

Choir et orchestra, Les Arts Florissants

See all the castSunday, December 21, 2008 - 4:00pm

Tuesday, December 23, 2008 - 8:00pm

Friday, December 26, 2008 - 8:00pm

Salle Favart

100, 85, 70, 40, 15, 6€

Cast

Actors, Luc Tremblais, Laurent Delvert

Choir and orchestra, Les Arts Florissants

Production, Opéra Comique

Coproduction, Théâtre de Caen, 9 et 11 janvier 2009

Partnership